02 Mar 2020

The number of newly confirmed COVID-19 cases in mainland China outside Hubei province (and not including imported cases) will drop to zero before 10 March, according to a mathematical model that correctly predicted when the daily newly confirmed SARS cases would drop to zero in 2003. This prediction for COVID-19 cases was made based on data collected through early February and has remained on track, said Professor Duo Wang of Xi’an Jiaotong-Liverpool University.

In January of this year, as news spread of the novel coronavirus infecting more and more people, Professor Wang dusted off the model he used 17 years ago to study the SARS outbreak. He and Professor Hefei Wang, director of the Financial Big Data lab at Renmin University of China, are using a slightly modified version to study the disease dynamics of COVID-19 based on data released by China’s National Health Commission.

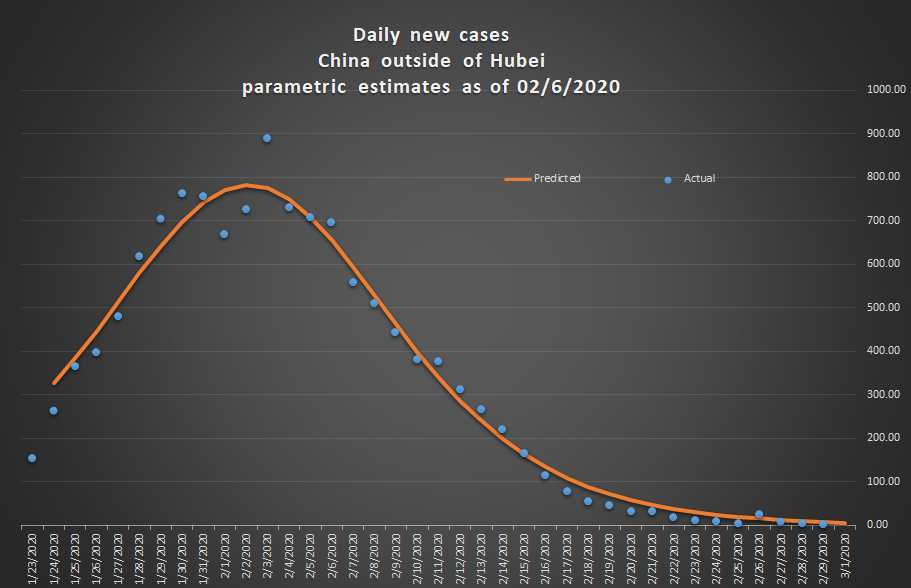

Actual newly confirmed cases number updated through 29 February. Parameters for the prediction curve were estimated as of 6 February. The model estimates the number of new cases for mainland China outside of Hubei (not including imported cases) will drop to zero between 7-10 March.

Professor Wang, of XJTLU’s Department of Mathematical Sciences, notes that factors could change the model’s forecasts.

“The model assumes a closed community. In a matter of weeks, several other countries have experienced new outbreaks of coronavirus,” he said.

“We need to keep up the stringent measures to prevent a rebound of the epidemic situation.

“In addition, we remain cautious about our model’s predictions because a large number of people have yet to return to work

“This might change the transmission probability, although with the current stringent measures put in place, we have not seen an increase in transmissions for the first batches of people who have returned to the workplace."

The professors’ COVID-19 model is estimated using data beginning 23 January released by China’s National Health Commission, including data from all of China except for Hubei province. Professor Wang said they decided to exclude Hubei province because its overwhelmed testing system in the early stage could result in data too inconsistent for this model.

After a couple weeks, the model began providing “stable and consistent parameter estimates,” or forecasts that turned out to be nearly on-target, he said.

“As of 6 February, we predicted the peak of the number of newly confirmed COVID-19 patients each day for China outside of Hubei province to be on 2 February, and that this number would drop to below 100 on 17 February,” Professor Wang said.

“Both of these turned out to be quite accurate. The peak – as of now – appears to have been 3 February and the number of newly confirmed patients indeed dropped below 100 exactly on 17 February.”

For both the SARS and COVID-19 outbreaks, Professor Wang used a classic SIR model, commonly used in modelling epidemics.

“It builds a mathematical model using a set of differential equations, describing the dynamics between three types of people in the population: those susceptible, those infectious, and those removed,” he said.

At the time of the SARS outbreak, Professor Wang was head of the Department of Financial Mathematics at the School of Mathematics at Peking University in Beijing, the city where the largest outbreak occurred.

“My research specialty is in differential equations and dynamical systems. Being right in the centre of the SARS epidemic, I decided to give this classic model a try,” he said.

“While many people use this model, the trick is on parameter estimation, since this set of differential equations does not have explicit solution – it is a numerical estimate.

“For the SARS model, we used an approximate formula of the SIR model for the number of newly confirmed patients for the parameter estimation.

“In addition, we excluded the infected medical workers from the data, since they tend to have a different transmission rate from the general population.”

This was important, Professor Wang noted, since the SIR model assumes that people in each of the model’s categories have the same characteristics as other people in that category.

Professor Wang and his colleagues tracked the SARS outbreak data from 23 April 2003 - 15 May 2003. They then released a paper about the model on 17 May to a special conference about that outbreak held at the Peking University medical school.

Their model indicated that the SARS newly confirmed infections would drop to zero between 15-18 June 2003, which he said surprised many.

“Our model’s prediction that the SARS outbreak would end in mid-June seemed quite bold at the time, and not that many people believed it would turn out that way," he said.

“It turns out that the SARS outbreak indeed ended in mid-June 2003, verifying that our approach had worked very well.”

This was about a month after The Journal of Peking University (Health Sciences) accepted his paper on the SARS modelling, he noted.

Professor Wang emphasized that, while the prediction of newly confirmed COVID-19 cases in mainland of China outside Hubei province dropping to zero in around a week is hopeful, the modelling process and forecasts are not set in stone.

“When the number of newly confirmed cases is small, there tends to be higher fluctuations as it travels down the curve,” he said.

"We want to stress that the work on the COVID-19 data is preliminary and our models and estimation approaches may change as we go along.”

By Tamara Kaup

02 Mar 2020

RELATED NEWS

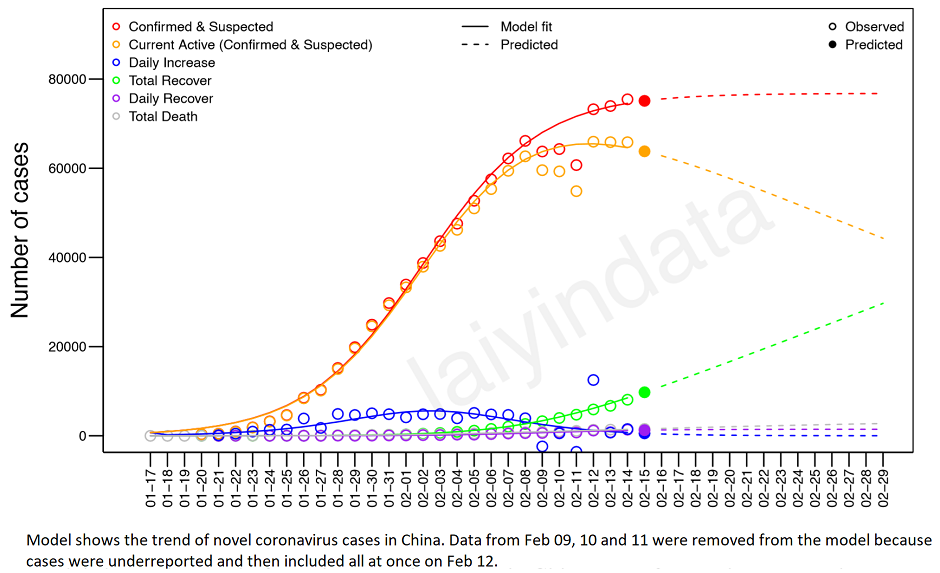

Model indicates current COVID-19 infections in China already declining

A mathematical model set up by an ad-hoc group of scientists indicates the number of currently infected novel coronavirus cases in China began a pattern of d...

Learn more